Karagula, Styx

Thursday 16th June 2016

Polymath playwright Philip Ridley is endlessly inventive. Having written a couple of exciting pieces of bravura storytelling — Tender Napalm (2012) and Dark Vanilla Jungle (2014) — he went on to pen a political comedy — Radiant Vermin (recently revived at the Soho Theatre) — about the housing shortage, with three actors directly addressing the audience, and now he’s back with yet another kind of play: this time it’s a truly epic fantasy in a found space. So prepare to leave the comfort of the West End and travel deep into north London to experience the weird and wonderful world of Karagula. Time to cross the Styx.

Named after the river in Greek mythology that separates Earth from Hades, the venue for this play is a former ambulance station located a couple of minutes from Tottenham Hale station, which provokes the thought that this Zone Three area is metaphorically hellish. The venue is a difficult-to-find open-air tented bar, complete with pizza oven, although the sense of being on the border between life and the Underworld is only apparent inside, where the stygian gloom is an aptly atmospheric environment for a play that is set in the distant or alternative future.

At first, the story concerns Mareka, a post-apocalyptic town that has been modelled on highly selective memories of 1950s American culture, with Prom Kings and Prom Queens, cheerleaders, milkshakes and, of course, apple pie. In a strange ceremony, which is gradually revealed to be part of the official religion (complete with holy writ, prophets and heresies), the assassination of JFK is re-enacted annually. As well as songs that boost the town of Mareka, there are rituals that test the faith of suspected dissidents, so look out especially for the dreaded Ziddigga jar. Ouch.

In a parallel storyline, another state, COTNA, solves the problem of social conflict from having competing religious beliefs by banning religion and family life all together. Imposing a clinically white-suited Orwellian regime, order is maintained by giving the inhabitants numbers instead of names, and destroying all evidence of the past, such as photographs, thus stamping out memories of history and older identities. The COTNA ruling class also have a ferocious weapon, blue light, to conquer any anarchic sects, such as the followers of the Holy Blacksmith Lord or the Sacred Red Biker.

What joins both Mareka and COTNA is the love story of Dean and Libby, two teenagers who rebel against authority and sow the seeds of doom for both oppressive states. They are aided by this fantasy world’s meteor showers, telepathy, radiation, mutation, odd births, pet wolves and weaponised giant lizards — anything is possible! At first, this epic story feels both confusing and familiar (satire on 1950s Americana), but gradually — like a vision emerging from the darkest mist — an edgy reality comes into focus. With immense skill, Ridley shows both the comforts and contradictions of organised religion and the human desire to believe. Religion is, at one and the same time, a deep need and ragbag of intellectual and symbolic ideas. And there is also a sense of wonder: what would you make of a snow globe if you had no experience of snow?

As in his 2012 play, Shivered, the narrative is fractured and thrilling. The piece is replete with vivid images and startlingly dramatic moments: quick episodes of unbelievable savagery smash the placid surface of assorted myths, as powerful metaphors of faith and belief collide with verbal glories. From highly disturbing passages about lynching or torture to grim accounts of domination and control, this is also a handbook for revolt on a futuristic planet. It’s totally absorbing and intensely fascinating, and like nothing else you’re likely to see. And the delicious thing about Ridley’s vision is its humour. Religious ideas, he suggests, are often the result of accidents and misunderstanding, and of such bizarre and random acts as an insect bite. A butterfly flaps its wings; somewhere, an empire crumbles.

Much of the joy, and of the sheer pleasure (why else go to the theatre?), of the Karagula experience comes from the compelling detail and density of Ridley’s fantasy landscapes. And quite a bit more can be derived from the genuinely mind-bending challenge of piecing together the entire narrative from the fragmented form of the play. I estimate that it takes more than a couple of hours to read and reread the relevant scenes (all of them!), but it’s worth it. Empires rise and fall, religions are created and destroyed, peoples move across the globe. Gradually, the sheer majesty of the work and its message becomes clear: you can try to stamp out religion, but it will always resurface; you can try to crush dissent, but it will always return.

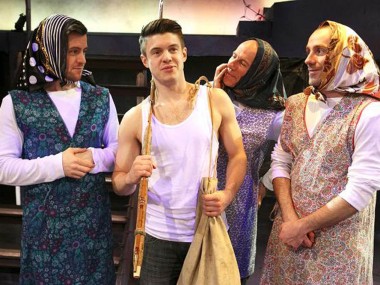

Hugely long, at more than three hours, with a half-hour interval in which the scaffold staging is changed from traverse to end-on, Max Barton’s production — designed by Shawn Soh — successfully uses a cast of nine to play more than 50 characters. If the director occasionally struggles for perfect clarity, the general effect of Karagula is to blow you away with its unique voice and massive ambition. A co-production with the Soho Theatre, this is a totally immersive mythological experience that is both amazing and exhilarating, with good performances by Theo Solomon (Dean) and Emily Forbes (Libby), plus Lanre Malaolu, Obi Abili and Lynette Clark to name but a handful of the impressively hardworking and versatile cast. Great stuff! Yes, this may well be my theatre event of the year!

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk