A brief history of in-yer-face theatre

Friday 1st July 2016

Whether or not it really is a foreign country, the past has a tendency to feel like it’s a long way away, and that it needs a tiresome journey to reach it. Years pass, and facts we took for granted slip across the horizon. Memories fade. Errors creep in. And oblivion beckons. Ever since the publication of my book, In-Yer-Face Theatre: British Drama Today, in 2001 it has been widely assumed that I was responsible for coining the phrase “in-yer-face theatre”. This is untrue. Not me guv’. Although I certainly was the first to describe, celebrate and theorise this kind of new writing, which emerged decisively in the mid-1990s, I certainly did not invent the phrase: indeed, I have made the point (more than once) that my choice of the label “in-yer-face theatre” — as opposed to “new brutalism” or “neo-Jacobean” — to describe this style of avant-garde new writing was precisely dictated by the fact that other people were already using the phrase. I did not impose it from above on an already existing theatre phenomenon; I extracted it from common usage. From below, so to speak. So when was the phrase “in-yer-face theatre” first used, and by whom? Well, the specific phrase “in-yer-face theatre” is derived from the general expression “in-yer-face” (often used as an adjective or exclamation in popular culture in the 1990s, sometimes in the more genteel form “in-your-face”). Every dictionary now has an entry for this phrase. As regards the specific label “in-yer-face theatre”, my research suggests that it began as an adjective used occasionally by theatre critics, was then turned into a rallying cry by at least one theatre-maker, until it finally matured into a publishing opportunity.

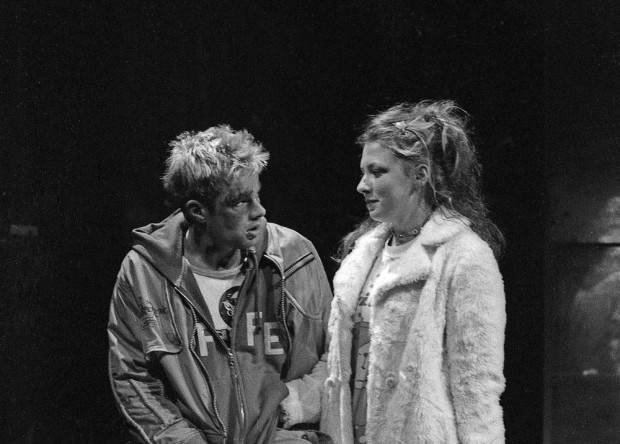

So first let’s hear from the critics. In April 1994, the Independent’s Paul Taylor reviewed Philip Ridley’s Ghost from a Perfect Place and described the play’s girl gang as “the in-yer-face castrating trio”. (Incidentally, in his review of the same show the Telegraph’s Charles Spencer used the phrase of “praying that you won’t part company with your supper”, an image he also used in his reviews of Simon Donald’s The Life of Stuff in 1993 and of Sarah Kane’s Blasted in 1995.) In the early 1990s, there was much less new writing than in subsequent years, and sometimes weeks went by with very few new plays, let alone in-yer-face ones, being reviewed. Be that as it may, in January 1995, Blasted opened in the Theatre Upstairs at the Royal Court, although no review used the phrase that had been suggested by Taylor. It’s tempting to call this an oversight, although it clearly wasn’t. Anyway, things got hotter with the arrival of the stage version of Trainspotting, that iconic Generation X story. When in March 1995, Trainspotting visited the Bush in London, Spencer wrote about the Bush’s staging of “dramas which reflect the violent fragmentation of our times”: “You may not like these in-your-face productions; but they are quite impossible to ignore.” When, later in the year, the play transferred to the West End, the Times’s Jeremy Kingston commented: “The two previous productions of the play brought actors within inches of the audience, and such in-yer-face realism is inevitably reduced when it is staged, this time by Gibson, for a tour of proscenium arch theatres.”

By now, a theatre maker also steps in. In November 1995, in an interview with Financial Times critic Sarah Hemming, playwright and director Anthony Neilson opined that “I think that in-your-face theatre is coming back — and that is good.” Interestingly, the implication is that this style of drama has already arrived: otherwise, how could it be coming back? Maybe Neilson was already seeing his back catalogue — Normal and Penetrator — in these terms. As far as I know, this seems to be the very first coinage of the term “in-your-face theatre”, and it certainly wasn’t the last. One year later, for example, a Christian theatre group, based in unholy Manchester, was set up, and called itself In Yer Face. It’s a lovely irony that its agenda was quite different from that of the young writers that were emerging on the new writing scene: “Renowned for communicating issues of faith, identity and life skills in a culturally relevant way, the company has long been committed to investing into the lives of young people…”, says its website.

Finally, it’s time for a publisher to spread the word. About a month after Neilson’s interview, Ian Herbert, critic and editor of Theatre Record, gave the expression “in-yer-face theatre” an enormous new lease of life, plugging several different variations of it in his ‘Prompt Corner’ column in Theatre Record. Happily, he chose the more direct “in-yer-face” formulation over the more staid “in-your-face”. His first foray was published in January 1996: “Last year’s in-yer-face theatre gets the welcome addition of in-yer-heart emotional commitment.” In the next issue, Herbert was talking again about “in-yer-face playwrights” and, anticipating critic David Nathan’s comment on Kane’s Phaedra’s Love, he also wrote: “it’s vital, engaged work, going on in tiny spaces where the actors are as likely to be in your lap as in yer face”. Even at an early stage, this style of experiential theatre was associated with small studio spaces. In March, Herbert was taking a historical perspective on the new young Turks, or — to give one of his preferred formulations — the “in-yer-face school”, commenting that veteran playwright Bill Morrison “was doing in-yer-face a decade or more ago”.

Then, in May 1996, came Kane’s Phaedra’s Love, her follow up to Blasted — and Theatre Record’s cover announced triumphantly “In Yer Face”. You can see why: after all, the Jewish Chronicle’s David Nathan’s review included the observation: “Kane, you will remember, wrote Blasted, last year’s sensation, with its baby-eating, eye-gouging, homosexual rape and a lot of other ‘in-yer-face’ activities. Phaedra’s Love is more ‘in-yer-lap’…”, while the Times’s Kate Bassett noticed how Kane’s play “is in our faces, almost literally as the cast thwack between clumps of seats”. By July 1996, Herbert is referring to the emerging young new writers as the “in-yer-face brigade” and, in the same month, the Financial Times’s Ian Shuttleworth calls the lipstick lesbian musical Voyeurz “so consistently in-your-face (to name only the most northerly region) that it fails utterly to arouse”. By the time Mark Ravenhill’s Shopping and Fucking opened at the Royal Court in October 1996, the expression was spreading rapidly: for example, the Guardian’s Michael Billington called Ravenhill’s play “a deeply uneven, in-your-face play.” By the final years of the decade, variations of the phrase were used again and again.

Examples include Herbert’s “This is the territory of Judy Upton, Sarah Kane and our own in-yer-face school (including Crimp himself in Attempts on Her Life)” and this summary of the decade by critic Robert Butler: “The rise of ‘in-yer-face’ drama took a play with three asterixes in the title to the newly-christened Gielgud Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue. Mark Ravenhill’s capacity to shock in Shopping and F—ing (1996) was never wholly divorced from a less appealing streak of puritanism. Blasted, the play that catapulted Sarah Kane to fame in 1995, played in a 60-seat theatre: a smaller seating capacity, that is, than a double-decker bus.” Oh well, size isn’t everything.

While all this was happening, the original phrase was a common occurence in popular culture. As early as 1991, 808 State named a dance track “In Yer Face”, and by 1996 the iconic single of the moment of Cool Britannia, the Spice Girls’ “Wannabe” included the lines: “So here’s a story from A to Z, you wanna get with me/ you gotta listen carefully,/ We got Em in the place who likes it in-yer-face,…”. In the Independent newspaper, several reviewers have used it in their descriptions of television shows in the mid-1990s. For example, “[Tony] Parsons sounded as if he were reading out an article from some in-yer-face publication over selected shots of proletarian degradation: peroxide shopgirls tottering down the street, young men at a karaoke night with pale, blue-veined bellies that plopped like haggises.” Or “And whether people want this in-yer-face style pantomime when they’re curling up in front of the box after work is another matter altogether.” It is idle to speculate whether the popularity of the phrase on the Indie’s arts pages helped bring it to the attention of theatre critics.

Similarly, the moniker spread through discussions of other art forms: interviewing the Girlie Show’s Claire Gorham in 1996, journalist Janie Lawrence wrote: “Scarcely the most helpful attribute for a show that has been touted as personifying in yer face girl power but is best summed up as the bastard child of Loaded and Blue Peter.” Or how about this review of the film Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet? “From the opening sequence of a television followed by a kinetic in-yer-face staccato of imagery, to the softer ballet-like camera work of the passion scenes between the two protagonists, R&J is definitely cinema of cool.” Or this from the BBC? “The Turner Prize could not have been won by a nicer fellow than film-maker Steve McQueen. Given the blanket coverage roused by beaten front-runner Tracey Emin’s in-yer-face stubborn stains, it is an irony that the prize should have gone to an artist who avoided publicity and let his work speak for itself…” And this: “But what he [Billy Connolly] is selling is still gritty, in-yer-face-Jimmy Scottishness for which there will always be a market as long as the English are shockable, Americans are prissy and third-generation Aussies are seeking an identity.” Not even the cops could escape, as this New Statesman piece makes clear: “He is likely to be younger, better educated (there are now 10,000 graduate cops), less deferential. His style is ‘in yer face’ and he considers himself ‘professional’, not in the sense a doctor is professional, but as a footballer is.” Last but not least, in his book on The English (1998), Newsnight broadcaster Jeremy Paxman describes Manchester’s Moon Under Water pub as “noisy, in-your-face and on a Saturday evening packed with hundreds of young men and women getting aggressively drunk”.

Not surprisingly, the idea of writing a book about in-yer-face theatre was originally Ian Herbert’s. After all, he had used the term several times in print. A former publisher, as well as a critic and editor of Theatre Record, he was in a good position to see a market opportunity. After the Royal Court revival of Jez Butterworth’s Mojo in October 1996, he spoke to Peggy Butcher, drama editor at Faber, saying that — in the words of his 2009 email to Sierz — he “had the germ of a book that would address what was by now an identifiable movement. I said I’d call it ‘In-Yer-Face Theatre’. Peggy was interested and asked me to put in an outline, at which point I realised that a book would mean actual work, something to which I am not accustomed. Your interest in new writing at the time made you an obvious candidate for the job, and I suggested to you that you take it on, while apologising to Peggy for pulling out and telling her that I thought I had found a very good replacement — you.” His ironic tone notwithstanding, it is clear why Herbert was too busy to embark on a book: not only was he editor of Theatre Record, but also Honorary Secretary of the Critics’ Circle and was about to be made president of the International Association of Theatre Critics.

Journalism, and that includes theatre criticism, is a thing of the moment; publishing takes time. A long time. Once the editor (Herbert) had put the critic (Sierz) in touch with the publisher (Butcher), it would have been great if things had moved fast. But they didn’t. For example, it wasn’t until about spring 1997 that Sierz started using the term “in-yer-face theatre”. In one article, published in July 1997 but written much earlier, he was still talking about new writing rather than in-yer-face theatre: “Despite regional gloom, London theatres produce so many smart and snappily written plays by 20-year-olds that the 1990s may one day be seen as a decade of great new writing.” However, it was when he came to write up a key event, David Edgar’s ‘About Now’ — the Eighth Birmingham Theatre Conference (held on 11–13 April 1997) — that he first started using the expression “in-yer-face theatre”. He used it in an article for the Independent and then in a report for New Theatre Quarterly. Sierz met Butcher at the ‘About Now’ conference but in summer and autumn 1997 he was still thinking of writing a much more general survey of theatre in the 1990s, including chapters on Shakespeare, classical revivals, physical theatre, as well as new writing. Only one chapter was to deal with what his draft called ‘From Old Country to Cool Britannia (in-yer-face theatre)’. The plan was simply to discuss Blasted, Mojo and Shopping and Fucking.

Some time in autumn or winter 1997, Sierz and Butcher talked more seriously about the book, although the journey from Herbert’s original idea to Sierz’s book contract was a rather long one. Early on, Butcher vetoed the idea of calling the book Cool Britannia, on the grounds that in a couple of years no one would have any respect for that label — and how right she was. In December 1997, Sierz was writing to Simon Trussler, editor of New Theatre Quarterly, about the idea of submitting “my next piece, on ‘New writing in contemporary British theatre’”, to him. In January 1998, he was telling an academic, Nadine Holdsworth, that “I am also putting together some sample chapters and a book proposal for a publisher, so thanks for your encouragement.” Then, in April 1998, Sierz got himself an agent, John Parker of MBA, and began to expand the chapter on in-yer-face theatre into a book proposal. In June, he went to the ‘European Theatre: Justice and Morality’ conference at the University of London’s Senate House, and gave a paper on “Shocking and Fumbling: Censorship and British Theatre Today”, which included an account of the censorious reception of Kane’s Blasted and Ravenhill’s Shopping and Fucking. This event was the first time Sierz had to defend the work of the 1990s experiential and in-yer-face playwrights against academic skepticism. In fact, when Sierz interviewed Kane on 14 September 1998, he showed her this paper and she commented on it. At that time, although many critics had been won over by her more overtly literary Crave, there were very few academics who took her work seriously. Apart from a couple of articles, and an interview in Heidi Stephenson and Natasha Langridge’s Rage and Reason: Women Playwrights on Playwriting, nothing had been published in the academy. It was a gap that Sierz was keen to fill. By August 1998, he had submitted a pitch to Faber & Faber about both a general book on British theatre in the 1990s and one on In-Yer-Face Theatre, and after Butcher said she preferred the in-yer-face pitch, they began discussing the structure and content. A contract must have been signed in August or September 1998. By then, Sierz was already busy reading plays, researching information and interviewing playwrights. In the end, and during the course of 1999, Butcher read two complete drafts of the entire book and gave detailed notes on its content. Meanwhile, Sierz’s first academic article about cutting edge new writing, ‘Cool Britannia? “In-yer-face” writing in the British theatre today’, was published in New Theatre Quarterly. This was based on that original chapter about Blasted, Mojo and Shopping and Fucking.

But the reason that Sierz wrote the book originally was not only because of the theatrical impact of the shocking new plays which exploded onto the London theatre scene in the 1990s, but also because of the interest shown by Herbert and Butcher, who both acted as his mentors. He also had some other inspirations: early on, he wanted to write a book similar to Martin Esslin’s The Theatre of the Absurd and to John Russell Taylor’s Anger and After. Likewise, he was fed up with seeing books by complacent British academics, which had titles such as Contemporary British Theatre, which were about people such as Edward Bond or Arnold Wesker or John Arden, playwrights who were surely no longer “contemporary” any more. Sierz still thinks that many academic books about theatre are worthless, full of jargon about theory and really thin on the meaning of plays and the experience of going to the theatre. So he clearly thought he could do better, and this antagonistic attitude sustained him during the time, in 1998 and 1999, when he was researching and writing the book. He had a point to prove, and that kept him going. He was also helped by David Tushingham, a critic and translator who had also edited a book called Live 3: Critical Mass (which featured extracts from what the cover called “the current EXPLOSION in British playwriting”, published in 1996). Some time in 1998 or 1999, Sierz had an email exchange with him in which he argued for the use of the concept of experiential theatre as the defining aesthetic of 1990s cutting edge drama, and Sierz had no problem with accepting this. It was, after all, Sarah Kane, who stressed the importance of this defining idea of compelling drama.

Sierz finished the book in January 2000, and it was published by Faber and Faber in March 2001. But by the time it came out, the phenomenon that it was describing had already begun to slide back into the past. Such is the fate of all contemporary interventions. In fact, Sierz has since argued on various occasions that the year 1999 (when Kane committed suicide) could be used as a convenient end date for the first, hot, phase of 1990s experiential theatre. And indeed, the passing years seem to support this suggestion.

By the 2000s, mentions of in-yer-face theatre became more and more numerous. Theatre makers embraced it, whether snarling with anger, as in Simon Gray’s Japes (“So that the verbs and nouns stick out — in your face. In your face. That’s the phrase, isn’t it? That’s the phrase! In your face!”), or with self-reflexive humour, as in April De Angelis’s stage direction in A Laughing Matter: “Act Two, Scene Three: In-Yer-Face Theatre.” In one interview in 2003, Bush supremo Mike Bradwell said, “The line between being exciting and offensive is a fine one, new writing must be provocative but we have to entertain. Relentless In yer face Theatre rapidly becomes tedious.” Writers have tended to be skeptical of the label. Joe Penhall, for example, says, “Yes, I was put in the book, there’s a chapter on me. He’s kind of opportunistic, Aleks Sierz — and he opportunistically wrote, ‘Joe isn’t really part of the in-yer-face crowd, but I want to write about him anyway.’” Ironically, having helped coin it and popularise it, Neilson soon grew sick of the label: in 2007, he wrote: “I will presume that you know about the ‘In-yer-face’ school of theatre, of which I was allegedly a proponent.” In the same year, however, journalist Brian Logan reminded us: “For the first decade of his career, Neilson was the myth incarnate. He pioneered the so-called “in-yer-face” theatre movement of the 1990s; Ravenhill and Sarah Kane were his protégés. His breakthrough play, Penetrator (1993), defined the decade’s visceral, blood-and-sperm theatrical mode. In 1997 he had a porn star defecate on the West End stage in The Censor. His 2002 drama Stitching involved Auschwitz, sexual role-play and a woman who sews up her vagina.”

By 2009, Frantic Assembly could look back and remember that “The term ‘In Yer Face’ theatre was already very popular at that time [summer 1995] and it was felt that, even looking at it [a dance move] diagrammatically in our notebooks, the idea was in danger of being ‘In Yer Face’ made terribly real.” Since 1996, the year that Herbert popularized the phrase, there has even been an In Yer Face theatre company, which suggests that this sensibility can be godly as well as unholy. Throughout the past decade, reviewers have continued their love affair with the phrase: “[Gregory] Burke’s meteoric rise and a higher rate of ‘****s’ and ‘****s’ per 100 words than Irvine Welsh make him a press officer’s dream, at a time when the brutalism of ‘in-yer-face’ theatre seems to be the sine qua non for a theatre wishing to appear young and relevant,” wrote one critic. In 2005, Billington wrote, in a review of David Eldridge’s Incomplete and Random Acts of Kindness, “Ten years ago, the Royal Court was the focus for what became known as ‘in-yer-face’ theatre.”

Other commentators valued the phrase as an index of the zeitgeist. For example, in his history of pop and rock music, nicely named Black Vinyl, White Powder, Simon Napier-Bell wrote: “This was the nineties — the ‘lottery age’ — the ‘in-yer-face’ age. Modesty and reticence were out.” In 2002, journalist David Lister assessed Channel 4’s The Tube: “Jools Holland and Paula Yates presented the coolest youth programme ever broadcast: irreverent, in-yer-face, image-obsessed, but with a saving sense of humour.” By 2007, the Sunday Times printed the following: “As soon as he came out of art school, however, he set about provoking the hell out of anyone who was watching with a series of creepy portrayals of masturbating men. The most memorable of these in-yer-face onanists, a blobby chap in a spooky painting called The Big Night Down the Drain, is apparently a portrait of the Irish poet Brendan Behan, who had turned up on stage in Berlin so drunk that he didn’t realise his flies were open. According to Baselitz, Behan’s dangling howitzer seemed to bring a sense of occasion to the event.” Thank you, Waldemar Januszczak.

And the wider population loved the idea of being in-yer-face too. One BBC messageboard reaction to the incident in 2001 when John Prescott punched a protestor inspired this reflection: “Despite clear video evidence, to the contrary showing an out-of-wellied crowd of about 30 disgruntled Welsh farmers, in five years there will be about 50,000 people able to tell you how they were there, in the front line of British politics’ ‘In Yer Face’ Years.” In 2003, Tony Thorne’s Buzzword Quiz had the following definition: “In yer face (end of British reserve and new enthusiasm/assertiveness in public and private behaviour) also terms like ‘up for it’, ‘upfront’, ‘go for it’ — slogans expressing aggressive individualist ambition and self-fulfilment. In yer face started as a phrase that was used to criticise aggressive behaviour. In black American street slang, you would hear ‘she was in my face’ or ‘get outta my face’ meaning that someone was being too assertive or intrusive or pushy. Now in media-talk and casual conversation it’s used almost approvingly, meaning very confident and powerful and uninhibited (and that last one is the clue — it’s the British throwing off their traditional reserve and shyness).” So, it’s part of our national character now. Other usages are understandable, if a bit bizarre. Two examples from 2005: “In Yer Face are a sussex based function/covers band offering a refreshing alternative to the traditional show band formula” and “IN YER FACE is a relaxed cruise club open from 6pm until 9pm every Monday and Wednesday”. And how about this for sports equipment: “Carlton In Yer Face Badminton Racket.” Great stuff. All in all, the past two decades were the years of in-yer-faceness, and theatre was certainly not isolated from the general temper of the times.

© Aleks Sierz, June 2009

- An earlier version of this account appeared on the In-Yer-Face Theatre website.