Dearest Squirrel: Johnny and Pam Osborne’s long-lasting love

Saturday 1st July 2023

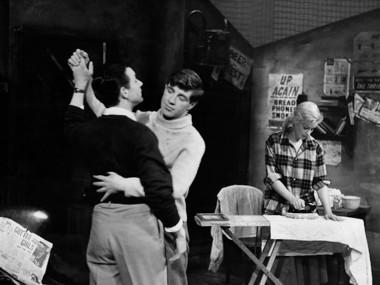

Look Back in Anger, John Osborne’s 1956 play, was a fertile cultural seedbed: out of it sprouted the Angry Young Men and kitchen-sink drama. What was less clear at the time was the extent to which it was autobiographical, based on Osborne’s failed first marriage to actress Pamela Lane. In the play, Jimmy, the working-class anti-hero, harangues his wife, the cool, emotionally distant and upper-middle-class Alison, attacking her parents and her class background. When Lane saw the play she immediately recognised this portrayal. When asked, many years later, about her reaction, she said: “I felt as though I had been raped.” The play was a theatrical version of revenge porn.

Peter Whitebrook, in his commentary on the young couple’s letters, retells the familiar story. Osborne, a second-rate actor and budding dramatist, met Lane while working at the Bridgwater repertory theatre in 1951. The pair fell in love, and, in the teeth of ferocious objections from her parents, married three months later. Both were 21 years old. Jumping on a train to London, they moved in with Anthony Creighton, an older friend of Osborne who collaborated with him on a couple of early plays, including Epitaph for George Dillon. Then Lane, a better actor than Osborne and twice as ambitious, managed to get a job at Derby rep.

During their separation, Osborne and Lane exchanged letters — which make up the early part of this collection — and they are sprinkled with young love’s typical endearments: she is Squirrel or Nutty and he is Bears or Teddy; Creighton is Mouse. But when Lane persuaded Osborne to come to Derby, arranging a job at the theatre for him, he was in for a shock. Despite the loving tone of her letters, she had started a relationship with a local dentist, who Whitebrook suggests was Joe Selby, a 48-year-old dental surgeon. Grotesquely enough, when Osborne went down with an agonising toothache Lane took him to her lover for treatment.

Most of this has been known for ages. Osborne gave his version in two volumes of autobiography published in 1981 and 1991, together called Looking Back, and subsequent biographers have added a bit of detail. What no one knew is that Osborne and Lane continued to keep in touch for decades after their divorce in 1957. And, as Whitebrook convincingly shows, they soon resumed a casual sexual relationship as well. So not only did Lane betray Osborne when he was her husband, but she also was party to his betrayal of his subsequent wives, especially his last spouse Helen Dawson, who he married in 1978.

Here is the emotional fuel of the book. What these letters reveal is that both Osborne and Lane were passionately involved with each other for decades, often mutually exasperated, but always drawn back to each other. Unable to live with each other; unable to live without each other. And, in the early 1950s, this was a cliché-busting story: here the man is the faithful homebody and the woman the sexual free spirit, a harbinger of the 1960s. Sexual liberation avant la lettre. And not only did Lane have affairs with men, she also had stable long-term relationships with women in the decades after her divorce.

Whitebrook’s edition of the couple’s letters is a dual biography of an obsession. But since neither of them were particularly expressive as letter writers there is, apart from occasional moments of crisis, little elaboration of what either was feeling. Most of the letters are about practical arrangements for meetings, congratulatory telegrams and quick notes, and the only major reveal is Osborne’s middle-aged passion for sexy lingerie. He often writes to Lane asking her to wear directoire knickers.

In many ways this is a sad book. Although Lane’s early career was much more promising than her husband’s she never made the big time. Most of her working life was spent in weekly rep, in yearly pantos, in theatres outside London, and in one-off television appearances. And she was often jobless and poor. For decades, Osborne sent her money — even when he owed the tax man thousands of pounds.

Whitebrook has done a good job in assembling the couple’s surviving letters, and in researching the background to their exchanges. Much of the book is his extended commentary on Lane’s numerous appearances in repertory productions of minor and major classics. This is specialist stuff. So unless you have a particular interest in knowing, say, what was playing on the stage of the Oxford Playhouse in spring 1965 (it was Julian Mitchell’s adaptation of Ivy Compton-Burnett’s A Heritage and Its History), then this is not an exciting read.

As a dual biography the book is definitive, but it does have a hole at its heart. Although Whitebrook has successfully put together the known facts about Lane’s private and public life, this fascinating, if somewhat restrained and reticent woman is strangely absent. Whitebrook makes some speculative comments, but he is no more successful at understanding Lane’s bisexual free-living spirit than Osborne was. Like Alison in Look Back in Anger, she remains elusive, an enigma in sexy underwear.

© This review of Peter Whitebrook (ed), Dearest Squirrel: The Intimate Letters of John Osborne and Pamela Lane (Oberon, 2018) first appeared in The Spectator, 31 March 2018.