That Face, Orange Tree Theatre

Thursday 14th September 2023

Playwright Polly Stenham had a meteoric rise with this play, her award-winning 2007 debut which she wrote aged 19 and whose original Royal Court cast featured Lyndsay Duncan and Matt Smith, and earned a much-lauded West End transfer. I remember it as a punky and powerful in-yer-face experience so I’m not surprised to see it being revived, this time starring Niamh Cusack, at Tom Littler’s ever enterprising Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond. Stenham went on to write Tusk Tusk, No Quarter and Hotel, and, despite the slenderness of her output, was awarded an MBE for services to theatre in 2020. But, since meteors — however bright — tend to pass quickly, can That Face still light up the contemporary sky?

The answer is yes and no. It’s a dysfunctional upper-middle-class family play that starts with an unsettling image: a young female has been hooded and tied up in what looks like a terrorist kidnap, but is in fact an initiation rite at a girls’ boarding school. When this ritual goes wrong, one of the bullies, 15-year-old Mia, is suspended and returns to her family. The trouble is that her parents — Martha (Cusack) and Hugh — are materially rich, but parentally incompetent. Martha has a severe drink-and-drugs problem and lives with their 17-year-old son Henry, who’s dropped out of school to become her carer. Hugh, meanwhile is in Hong Kong with wife number two. Not much use as a dad.

In fact, Martha is more of a child than Henry, and he has to become her parent in a reversal of family roles which is also incestuous, as well as jagged with jealousy and loud with resentment. Memorable incidents include the revelation of Henry’s cut-up clothes, a telephone conversation with the speaking clock and a splash of onstage urination. It’s punky and extravagant, but what’s less strong is any sense of psychological depth, any backstory, any exploration of the situation that goes beyond the surface antagonism of the characters. It is, and can only be, a young playwright’s first attempt, an over-hyped apprentice work.

In my memory, Stenham’s writing has an exhilarating fierceness, and her text rings loud with addiction, abuse and aggravation. On this occasion, I thought it is also a bit too explicit and too explanatory. On the plus side, she is equally sympathetic to both her older and younger characters, and her portrait of mother Martha is emotionally powerful, emphasising her chronic neediness and deep vulnerability. Like her image in a distorting mirror, Henry is out of his depth, trying to help but unable to satisfy his mother’s deepest longings, while the underwritten Hugh is fatally distant. Mia, unsurprisingly, is a bit lost, having been given little parental guidance. Yes, a damaged rich older generation hands down misery to its children.

Over the course of some 95 minutes, the central theme of codependence between parents and children is rather too emphatic, too underlined. Still, the school bullying scene is notable for Mia’s indifference to the plight of the 13-year-old victim of the older girls, while the dorm leader Izzy is convincingly self-centred and cynical. Some of the chat about hierarchies at public school is promising, but underdeveloped. On the other hand, occasionally Stenham introduces a queer sensibility, as when Martha assumes that Henry is gay because she sees him as artistic and gentle, and gender fluidity is indicated when he finishes up by wearing female clothing.

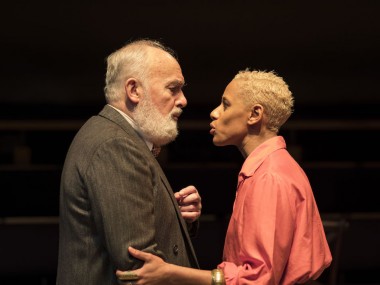

As directed by Josh Seymour, the play blazes away, sometimes a bit fitfully, with Cusack becoming rather too rapidly frenzied for my taste, although her later scenes with newcomer Kasper Hilton-Hille’s excellently pained and desperate Henry are emotionally taut. And moving. Another stage newcomer, Ruby Stokes, gives Mia an apt sense of indifference and neediness, and Sarita Gabony as Izzy is suitably arrogant. Dominic Mafham does his best with the slender part of pompous Hugh. Designer Eleanor Bull’s set is dominated by a central bed, which restricts the movement of the cast, and George Dennis’s soundscape suggests a gothic horror show. In the end, this revival proves that meteors rarely shine as brightly on their return.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk