Adler & Gibb, Royal Court

Thursday 19th June 2014

Theatre-maker Tim Crouch has a thing about art. One of his plays, ENGLAND, was performed in art galleries across the world; another was called An Oak Tree, after the 1973 conceptual art piece by Michael Craig-Martin. In fact, Crouch even looks like an arty type. Now, in his latest production, he tells a story about two fictional artists: Janet Adler and her lover Margaret Gibb. But, really, his main theme, as ever, is the relationship between art and reality, theatre-makers and spectators.

The audience arrives to see a bare set, on which two young kids are playing, with the bare-brick back wall of the theatre visible. There is a table at one end with the props, and a stage manager follows the action in the script. Then a Student approaches a lectern in front of the stage; she is giving an academic presentation about the now-dead Janet Adler, who was something of a radical anti-artist — destroying her own work; eating a critic’s painting; presenting a real puppy as an art object.

When the Student pauses to show a slide to illustrate her presentation, what we see on stage is not a projection of the slide but Sam and Louise, a director and actor who plan to find the abandoned house where the two elusive women used to live — and make a film about them. From the off, it’s a strange project: Sam coaches Louise to play the part of Adler, and both are clearly surprised when they discover that Gibb is still alive.

This simple story gives Crouch the chance to joyfully satirise academic descriptions of artistic creativity, and to comment on how film-makers, art critics and biographers vampirise the lives of artists. But as well as laughing at the blood suckers who slurp the essence out of creativity, Crouch also explores the nature of theatre, and theatrical representation. The two kids on stage play a variety of roles — from a deer to a dog to a corpse — but never in a literal or representational way.

In this show, there are many objects on stage, but they rarely stand for what they are in the story: a bit like conceptual art really. At various moments, Louise almost becomes Adler, wearing the dead woman’s clothes, imitating her accent. In fact, for the audience, what is the difference between watching an actress playing Louise playing Adler and watching an actress playing Adler? Likewise, the actor playing Sam has a Scottish accent, although he is meant to be an American.

In the second half of a short evening the story takes a couple of disconcerting leaps, and things turn very ugly. After a delicious parody of the grave scene in Hamlet, the unpleasant ambitions of Louise take centre stage. And her thoughts are more shocking than the shallow grave that the creatives dig up. So far so good, but the imaginative staging is not quite fast-moving enough to prevent you noticing some holes in the plotting — unless everything we see is a dream, or a complete fantasy (which I always feel is a bit of a cop out).

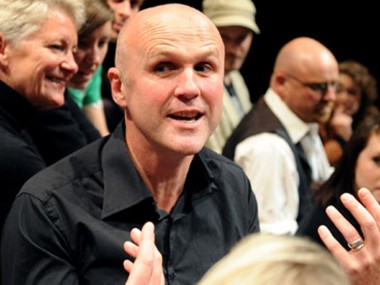

Actually, I loved this show until the final minutes, when I got the distinct feeling that Crouch’s ideas had run out of steam. The Student’s presentation finishes weakly; the final filming doesn’t really make sense; and the arrival of the big screen is a distraction from the theatricality of the rest of the piece. Of course, I know that Crouch is comparing art forms, placing literal views of reality next to conceptual ones, but somehow the last part of the evening feels like the playwright is just doodling in the margins. Before then there is plenty to enjoy in this production by Crouch, who along with Karl James and Andy Smith also directs on Lizzie Clachan’s set, and the cast is committed and playful: please take a bow Denise Gough (Louise), Brian Ferguson (Sam), Amelda Brown (Gibb) and Rachel Redford (Student). So while it’s great that the Royal Court is investigating the nature of theatre with such passionate verve, it’s a bit sad that good old-fashioned storytelling has stumbled somewhere by the wayside.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk