The High Table, Bush Theatre

Friday 14th February 2020

Queer people of colour face a double discrimination: racism and homophobia. Against this sickness of negation and stupidity one of the best antidotes is a culture of celebration. And in this project theatre can play its part. At the Bush, last September, artistic director Lynette Linton’s revival of Jackie Kay’s 1986 play, Chiaroscuro, in the form of a pleasurably lively gig, injected a heady dose of exciting music and poetry into a story about two young black lesbians. Now Linton is staging The High Table, a powerful and moving debut by new playwright Temi Wilkey, whose plot revolves around a gay marriage. And it’s a great show!

Set in London, Lagos and the afterlife, the heartfelt story concerns Tara and Leah, a young lesbian couple who decide to get married. But when they visit Tara’s Nigerian parents, mother Mosun and father Segun, to tell them the news, their reaction is negative. Very negative. For example, Mosun’s belief is that homosexuality is “an abomination”, while Segun has anxieties of his own which prevent him from supporting his daughter. His brother Teju, who still lives in Lagos, has been arrested after spending an evening in a gay club — and he needs to be bailed out. Can Segun overcome his own homophobia to help Teju?

As well as this terrestrial drama, which is disarmingly simple and yet emotionally true, there are several scenes set in the afterlife, somewhere in the sky, where Tara’s long-dead ancestors — Yetunde, Babatunde and Adebisi — debate whether to bless her same-sex union, or to oppose it. This fantasy element allows the playwright plenty of room to discuss ancient prejudices and to give a historical perspective on same-sex attraction. Before the coming of the white Europeans, and their Christian gods, the relationships of African women with women and men with men did not carry such a negative charge — and were not labeled and condemned by religion. This idealized view of African history may or may not be true, but it lends the play a wonderfully warm glow.

In fact, in the first half of the evening, Wilkey writes in a bright comic style which flings one-liners and sharp jokes into the audience, and these are greeted with roars of laughter and approbation. Frankly, it’s a bit soapy and simple, but the exchanges between parents and children are so well-observed and recognizable that it’s no problem to forgive some of the awkwardness of the dialogues or their occasionally didactic quality or the erratic jolts of the plotting. In the second half, the tone gets darker and more tragic because just as Tara and Leah run into trouble, Teju experiences the ghastly effects of homophobia in Nigeria. But as well as becoming more serious, the emotion of the show deepens, and the ending is thoroughly moving. As you’d expect, the curtain call is followed by a dance sequence as exciting as it is energetic.

The High Table — whose title encapsulates mother Mosun’s wish to dominate her daughter’s wedding in a traditional manner — is an original, rather rough but openly entertaining piece of theatre that appeals on a whole number of levels. I love the scene when the young couple practice dancing and the good-natured jokes about “African time” in the afterlife. The metaphor of disease to describe homophobia is strongly articulated and the painful personal moments well handled. The faint suggestion that homosexuality might run in families is not stressed, but the longing of gay people for family support comes across with great power. There is also a very attractive element of tenderness in the central relationship.

Although the story is straight-forward, Wilkey has created an atmosphere of psychological complexity by paying attention to uncertain feelings as well as to overt prejudices. The queer Nigerian British female experience is, the piece argues, inherently complicated and, sometimes, very confusing. For a start, lesbians from the African diaspora are not as visible as other social groups and various social stereotypes conspire to make coming out a difficult process. At one point, Tara and Leah compare notes about the emotions that surfaced when they told their families about their true personal identity. But if families are always a difficult place to live, the play is also finally quite optimistic: love is beauty, beauty love.

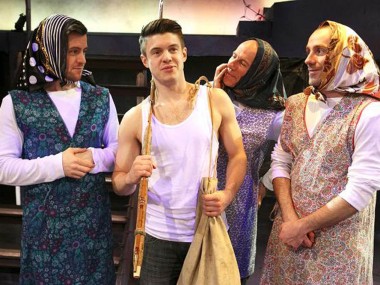

Daniel Bailey’s vigorous and enjoyable staging, a co-production with Birmingham Rep, is designed by Natasha Jenkins on a mountain-top set which features few props but has to be periodically and symbolically swept by one or another of the characters, and the evening features some very expressive performances. Cherrelle Skeete (Tara) and Ibinabo Jack (Leah/Adebisi) are both gently loving and lovingly disputatious, while Jumoké Fashola is thrillingly majestic as both Mosun and Yetunde. As the brothers, David Webber (Segun/Babatunde) and Stefan Adegbola (Teju) work well together and in one scene the sparks really fly. The actors who play the two gay characters of this family don’t double up so this creates a sense of their isolation. At the same time, the atmosphere of the piece is greatly aided by percussionist Mohamed Gueye, whose drumming is great for your heart beat. This play is sexy, spiritual, idealistic and has its heart in the right place: party on!

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk