Gloria, Hampstead Theatre

Thursday 22nd June 2017

This play’s subject is alienation, at work and in the home. (But mainly at work.) In contemporary society, office work seems to symbolize a life of modern drudgery. Poor pay, poor conditions and poor prospects suggest that this kind of wage slavery — and in the case of interns, unwaged slavery — is part of the fabric of our oppression, and of our alienation from the means of our self-fulfillment. In American playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s 2015 piece, Gloria, this feeling comes dramatically alive.

The first act is set in the offices of a cool Manhattan magazine, and opens to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach: the Gloria section of the Mass in B Minor. Its wonderful tumult contrasts vividly with the four cubicles on stage, work stations for a dissatisfied workforce, a group of office assistants. There’s Dean, who’s almost 30, and whose ambitions to become a writer seemed to have stalled in this slough of arts journalism. Around him clings the smell of a hangover, of too much drinking, and of failure. When his boss, Nan, calls him into her office it is to ask him to dispose of a plastic bag into which she has just thrown up. It’s not exactly a job that Ernest Hemingway would do.

Opposite him is Ani, a good-hearted but nerdy computer expert who has put her special skills on hold while she tries to make it in the super-competitive world of journalism. Occupying the other two cubicles are Kendra, a bright if vicious Asian-American journalist who prefers shopping to writing, and spends a lot of her time at work popping out to the local Starbucks, and Miles, the black company intern, who listens to music on his headphones when he’s not making a run to nearest vending machine, a slave to the whims of the others.

All the anxieties of office life in the wonderful world of journalism are here. These young people are cynical, with a kind of brittle wit that sounds more clever than profound. They nurse their private dreams of success and work hard at their rivalries. Their ambition clings to them like the post-it notes on their screens. But can be as easily blown away. Amid the satirical comedy, there are some serious points. They all realise that their generation will have less prospects, less income and less success than their predecessors from the baby-boomer years. But they are all too resigned to do anything much about it, except to bitch and bollock each other.

As they bicker and banter, two other office workers pass through from other departments: one is the veteran fact-checker Lorin, a man so steeped in disillusion that his tongue is permanently dry. The other is Gloria herself, the most unpopular woman in the office, a sad case of a person who has dedicated their whole life to their place of work, only to find herself pissed on not only by management, but by her colleagues as well.

I can’t tell you what happens next because that would be a massive spoiler, and the theatre has even glued together four pages of the programme to prevent audiences reading about this, so let me instead use a metaphor. In Act One, Jacobs-Jenkins brings a kettle slowly to the boil, gradually blocks its spout, and then watches as it explodes. And boy, what a bang.

Act Two is all about picking up the pieces. With even more satirical bite, Jacobs-Jenkins shows how the different characters react to what has happened. Dean, for example, tries to incorporate it into the memoir of office life that he is writing, and the exploitation of bad stuff by ambitious writers and journalists blossoms like some evil fruit throughout Gloria’s second half. But exploiting experience soon hardens into frantic competition, as more and more characters try to do the same.

At the same time, this remains a study in alienation. People who were simply glimpsed in the background come to the fore, and we are reminded of how often in offices we take other workers for granted, as we toil shoulder to shoulder with strangers. The difficulty of knowing exactly who the other person is, emerges from the shadows as a powerful theme, closely followed by the realization that this is just a mircrocosm of the playwright’s criticism of post-industrial consumer capitalism. Shades of Martin Crimp here, as well as of Caryl Churchill.

But however enjoyably astringent, Gloria is not a perfect play: it asks us to accept that random terror is inexplicable, and that seems a touch reactionary, and it pictures all of its women as viciously ambitious, while its men are often lame and sometimes even sensitive. At one point, the experience of maternity allows one of the journalists to get a foot on the ladder to television, which vampirises the lives of the others. Despite the playwright’s intelligence, all this leaves a slightly nasty taste.

Still, Michael Longhurst’s pacy production, using Lizzie Clachan’s stylish designs, glows with a humour that is both perceptive, and a bit sick. Most of the cast play several roles, with an increasingly desperate Colin Morgan (Dean) going off the rails, a motormouth Kae Alexander (Kendra) doing her thing, plus Sian Clifford (Gloria/Nan), Ellie Kendrick (Ani), Bo Poraj (Lorin) and Bayo Gbadamosi (Miles). Well-observed and sharply critical, this is also an evening of fun. But remember its awfulness the next time you pick up a magazine.

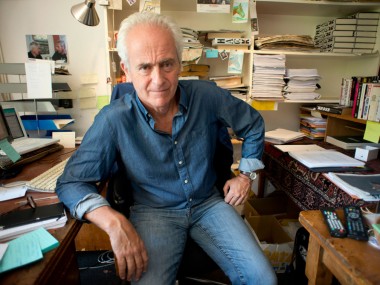

© Aleks Sierz