Trouble in Butetown, Donmar Warehouse

Monday 20th February 2023

With the fast-approaching anniversary of the latest war in Europe, our culture’s continued fascination with the second world war gets a contemporary boost from Trouble in Butetown at the Donmar Warehouse. Written by Diana Nneka Atuona, this follow-up to Liberian Girl, her 2015 debut, won the 2019 George Devine Award for most promising playwright. Although it revisits familiar territory, and adopts a deliberately traditional theatre form, it includes an interesting slant on race, multiculturalism and the Special Relationship between the UK and the USA.

Set in Butetown, or Tiger Bay, a port area in south Cardiff with a history of multiculturalism, the background of the play is the arrival of American soldiers to help defeat the Nazis in Europe. But although they were part of the Allied push to eradicate fascism, they brought their own prejudices with them. Because of the racially segregated society of the Southern states, white and African-American soldiers were divided into separate platoons, housed in separate barracks, and had separate food and medical staff. They came accompanied by the Jim Crow laws. So in Cardiff, in this early 1943, socialising with locals is forbidden, and the vicious white-helmeted military police (known as “Snowdrops”) keep control.

We are in an illegal guesthouse run by the redoubtable but impoverished Gwyneth, who supplements her income by distilling vile alcoholic spirits in the backyard, the story begins with a tableau of her tenants: old sea-dog Patsy, Jamaican sailor Norman (who quotes Marcus Garvey), and Dullah (a Muslim who loves drink as much as the Quran). Gwyneth is a war widow, and has two half-Nigerian daughters, the teenage Connie and little Georgie, who loves her absent father, a boxer in civilian life, and who dreams of making a heroic contribution to the war effort. She gets her chance when she bumps into Nate, an African-American soldier from Georgia, in hiding from the military police.

This rather charming slice-of-life comedy, in which even the arguments between the residents are good-natured, becomes a drama of ethical choice when Gwyneth discovers Nate’s presence. The household have to decide whether to hand him over to the authorities, especially after a handsome £50 reward is offered, or help harbour him as a fugitive. Connie, who wants to leave home and her ever-vigilant mother to join up as a singer and entertainer of the troops, is attracted to Nate, while her best friend Peggy is in love with Dullah. Since Nate is a wanted man and Dullah has been lined up for an arranged marriage, both women also have to decide on how to do the right thing.

There is a lot of fun in some scenes, especially when little Georgie is involved, but the overall theme of people’s inherent goodness in this multicultural environment does smooth out a lot of the conflicts, although there is a very strong moment when Norman confronts Nate. The piece’s vision of a large extended family, which is mixed and yet mutually supportive, is rather idealistic — as is the traditional theatre format of a well-made play. Some of the plotting is a bit clumsy, and a rather tender story about Nate and Connie’s love is uncomfortably squeezed into the bigger drama, while the parallel strand about Peggy and Dullah is underwritten. Also, relying heavily on the rather cute figure of Georgie does introduce an unnecessary sentimentality to the show.

And that’s not all. There is likewise something a bit disturbing in the central ethical proposition that killing a racist, even in self-defence, is somehow okay, although Atuona does make Nate suffer for the fact that his best buddy has been punished for something that Nate himself was responsible for. Despite the fact that the arrival of an American military policeman and a Welsh cop raises the stakes, Gwyneth’s danger — arrest for harbouring a fugitive and prosecution for an illegal guesthouse and selling dangerous alcohol — is rather downplayed, and none of the other characters seem to be risking much. The smiles of comedy mask the pains of the past.

So although Trouble in Butetown reminds us strongly of the overt racism of the 1940s, and does a good job in showing some of the fun of a traditional community — Connie’s love of singing is twice beautifully demonstrated — the play never really takes off. This is partly because neither Atuona, nor her director Tinuke Craig, are able to sufficiently animate the large cast scenes, which often turn out to have two characters speaking while the rest sit around mutely watching. Not very realistic. Despite these drawbacks, it has to be said that this is a warmhearted evening, performed on a finely detailed set by designer Peter McKintosh and with some lovely music by Clement Ishmael.

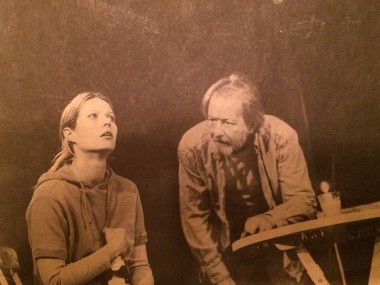

The cast features some agreeable performances, with Sarah Parish’s tough Gwyneth — whose scowl can curdle milk — dominating the menfolk: Ifan Huw Dafydd’s tolerant Patsy, Zephryn Taitte’s drink-loving Norman and Zaqi Ismail’s Dullah. Both Rita Bernard-Shaw (Connie) and Samuel Abewunmi (Nate) make their stage debuts, with the former in fine singing voice. Ten-year-old Rosie Ekenna, also making her stage debut, is Georgie (sharing the part with Ellie-Mae Siame), a bundle of energetic fun that does a lot to encourage audience sympathy for the whole production. Some humane and funny moments help smooth out the bumps in the writing — it all makes for an entertaining show.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk