The Lehman Trilogy, National Theatre

Thursday 12th July 2018

Images are what make abstract crises concrete. And who can forget the image of the bankrupt Lehman Brothers’ employees leaving both their New York and London headquarters carrying their personal possessions in grey cardboard boxes on 15 September 2008? The global financial crisis, which involved the difficult concepts of weird and wonderful debt-creating instruments, had suddenly acquired a human dimension. This image is at the heart of Sam Mendes’s brilliant staging of Italian writer Stefano Massini’s The Lehman Trilogy, which in this version comprises three parts which run for more than three hours and have just three cast members, including British national treasure Simon Russell Beale.

With astonishing ambition, the National’s Ben Power has adapted the plays into a single evening that focuses not on the financial giant’s collapse in 2008, but on the 160 or so years of the firm’s history, charting the amazing story of one German-Jewish migrant family and its success — phenomenal success — in America, the land of freedom and opportunity. Starting on 11 September 1844 (what a resonant day and month!), with the arrival at Ellis Island of Hayum Lehmann, son of a cattle merchant in Rimpar, Bavaria, the first part — called Three Brothers — tells the story of how he changed his name to Henry Lehman and settled in Montgomery, Alabama. Joined by his brothers, who also Anglicize their names to Emanuel and Mayer, Henry expands his two-dime store into a flourishing cotton transportation business.

As these middle men become efficient cotton brokers in the South, they survive plantation fires, the American Civil War and eventually turn themselves into a bank (with the state governor’s support). By the time of the second part — called Fathers and Sons — Lehman Brothers has moved to New York and the family expands as Emanuel and Mayer marry and set their children up in the business. By part three — The Immortal — new Lehmans, Philip, Herbert and Robert, take centre stage, investing in railways, the Panama Canal and Hollywood. Despite the Wall Street crash of 1929, the company survives, becomes a multinational corporation, and brings in non-family outsiders to modernize and expand its business. Enter Lew Glucksman, Pete Peterson and Dick Fludd.

As Professor Sarah Churchwell writes in a programme note, the Lehman dynastic saga is not a simple example of the American Dream, a phrase that originally in the 1930s meant not material gain, but spiritual improvement. Massini and Powers show how the Jewish heritage of the clan is gradually compromised as family members sit shiva for decreasing amounts of time when their relatives die: for Henry, there’s a week of mourning; for Robert just three minutes. Money never sleeps. The ceaseless pursuit of financial gain has turned everyone into workaholics who now longer care about self-improvement — all they want is profit, profit and more profit. Although the tone is never preachy, the message is clear: finance capital consumes the Lehman family well before the final crash of 2008, when the corporation collapsed.

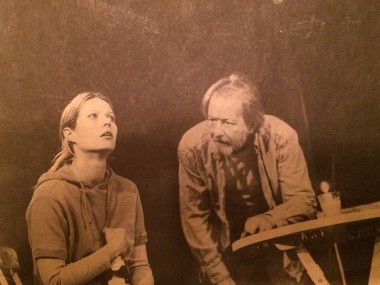

Watching this American epic unfold over a long evening, with two intervals, a feeling of sublimity is aroused by Mendes and his flawless cast. Beale begins as an almost majestic figure, Henry the original arrival, narrating with dignity the family’s humble background and their early Alabama days. His tone is homely, serious, but with occasional waspish asides. Later, he plays Philip and a series of cameos: a Wall Street tightrope walker (wonderful metaphor), a blushing bride, a strict rabbi, and an alluring divorcée. His often mesmerizing performance is perfectly balanced by those of Ben Miles, as the irascible Emanuel, and Adam Godley as the milder Mayer, who acts as a buffer between the two brothers. All three then play dozens of other characters.

Much of the sheer joy of the evening comes from seeing these actors at the very top of their game. At one point, Godley plays the love interest Paulette, who responds to courtship with the repeated phrase “annoyed, amused, curious”, which he illustrates with tiny hand gestures and a lifting of the eyebrows. Later, he pops on a pair of square sunglasses and becomes the single-minded Robert, metaphorically dancing himself to death as financial services expand with dizzying speed in the 1960s. Miles, a great foil to Godley’s comic grimaces and Beale’s magnetic presence, plays the same range of roles: at one point he is a rebellious child, who argues with a rabbi while the other two impersonate a large variety of children. It’s hilarious. Rarely has a simple shrug, or the curl of a finger or lip, been more expressive. The acting is so fluid, so confident and so unforced that it sometimes seems that a maestro such as Peter Brook is hovering above the stage. This really is a sublime show.

Mendes and designer Es Devlin set the three parts in a modern glass-walled Lehman office, which rotates as the actors pass from room to room, place to place, age to age. Under strip lighting, they use the instantly recognizable office boxes as all-purpose props: bales of cotton, chairs, a street card player’s table, Wall Street, while in the background Luke Halls’s video projections in black and grey and white evoke burning plantations, the construction of the Empire State building and the 1929 crash. There are no costume changes so the three frock-coated actors gradually seem more and more like ghosts from the past, haunting our current world. Crucially, the tale is accompanied by music director Candida Caldicot’s piano playing. All in all, it’s minimalism rendered magnificent.

Power’s version not only tells the story in massive detail — the evening is one huge long narrative, told by the actors in turn, and only occasionally giving glimpses of dialogue or conflict — but also emphasizes the uncanny madness of rampant capitalism, while simultaneously showing how each of the Lehmans was haunted by good dreams and bad dreams. The story culminates in the delirium of trading as the Goddess of the Market does the Twist, computer screens flash and buzz, and incantatory phrases (a key feature of the evening’s pleasure) are repeated. Vivid images — Henry is the family’s head, Emanuel the arm, Mayer a potato — are both amusing and memorable. Breezes repeatedly caress ears, trust is repeatedly invoked and the magic of money shines even in the gloom.

Of course, purists might object that there is no play here. It is just a massive narrative, told in paragraph after paragraph of journalistic storytelling. It’s more The Power of Yes than Enron. Likewise, the realities of exploitation, of money-lending to slave owners and of imperialistic expansion are rather glossed over in this optimistic sweep of an epic, which mixes little drops of humour into the grand design, almost a fairy tale, or morality play, of the rise and fall of a capitalist family’s fortunes. But the clarity and resonance of the writing turns the tale into art, and the quality of direction, design and, above all, the magnificence of the acting, make this one of the best theatre experiences of the entire year. It justifies any hyperbole.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times

1 Comment

on Thursday 25th July 2019 at 10:47 pm