The Lieutenant of Inishmore, Noël Coward Theatre

Thursday 5th July 2018

Actor Aidan Turner, who plays the Cornish land-owner Poldark in the hit BBC series of that name, now makes his West End debut in a comedy about terrorism that is as dark as a dried blood stain. First staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2001, about four months before 9/11, Martin McDonagh’s play is a gore-spattered Irish tale from the bad old days of The Troubles, and one whose wild hilarity and theatrical Grand Guignol is as likely to punch you in the face as tickle your ribs. As directed by Michael Grandage, whose revival of John Logan’s Red is just around the corner at the Wyndham’s Theatre, The Lieutenant of Inishmore proves that some black humour doesn’t age.

Set mainly in a cottage on Inishmore, one of the Aran Islands off the west coast of Ireland, in 1993, the play tells the story of 40something local man Donny and young Davey, a neighborhood teen who has hippie-length hair and rides a pink bicycle. Because the community is small, they know each other very well, and when Davey brings in the mutilated body of a black cat, Donny is incensed that he has killed — by careless bike riding! — Wee Thomas, the lifelong pet of his son, Padraic, who is currently away from home, having joined the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), an extremist splinter group from the already extreme Irish Republican Army (IRA), both fighting the British army in order to expel the Brits from Northern Ireland.

Padraic, known as Mad Padraic, is a self-styled lieutenant and is dangerously out of control, and we see his psychopathic tendencies in action as he tortures James, a Northern Irish drug dealer. But as well as being vicious the crazy terrorist is also sentimental, and when his father phones to tell him that his cat is sick (omitting the news that he is actually dead), he pumps his mobile phone full of bullets and decides to return to Inishmore. On arrival, he bumps into Mairead, a cropped-haired 16-year-old who is Davey’s sister and who dreams of leaving the backwater and becoming a freedom fighter. Although Padraic rejects her advances, he might well benefit from her Annie-Oakley-style sharpshooting skills when three INLA operatives arrive who, fed up with Padraic’s freelance ways, decide to execute him.

Written with a dazzling freshness and a joyful love of language, the play satirizes the rhetoric and fanatical single-mindedness of the Irish Republican movement by aligning its aim of a free united Ireland with the ideals of a cat-loving psycho. There are genuinely hilarious discussions about the morality of killing cats, which echo the clichés terrorists use when talking about human casualties, and speeches which have scant respect for the Republican cause, such as Padraic’s “All I ever wanted was an Ireland free… Free for cats to roam about!” What McDonagh skewers so savagely is the sentimentality of the whole nationalistic worldview.

The playwright uses cats to comically comment on the traditions of rebel songs, misty-eyed nostalgia for a Gaelic past and political aspirations that have become locked inside the barrel of an Armalite rifle. One of the INLA men asks: “Is it happy cats or an Ireland free we’re after?” It is writing that is dangerously disrespectful to the militant fighters of both sides, and to their victims, and there are a number of jokes about real-life bombings, assassinations and other atrocities that are clearly in questionable taste. But, at the same time, McDonagh is successfully treading the tightrope between satirical criticism and a visceral agony he feels about the sheer waste that results from violence. He hates killing, even when he biliously laughs about it.

Originally written early in McDonagh’s now starry career (his film Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri won two Oscars this year), the writing has a freshness and creative brio that is dazzling and the plotting of the story is sublime. As the programme to this excellent West End revival says, setting the story in 1993 enables the playwright to make references to numerous acts of Republican violence, even as the peace agreement was being hammered out. But the 1990s was also the era when Islamist violence first became evident, and there is a temptation to see the play as somehow speaking to the concerns of the War on Terror. This would be, I think, a mistake, as Islamists are not so much sentimental as suicidally fanatical, which is not the same thing.

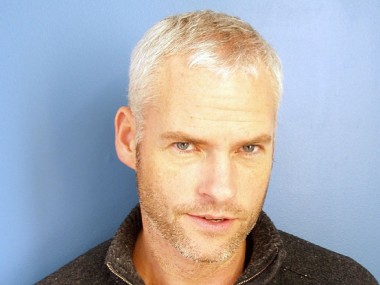

As you’d expect, director Grandage and designer Christopher Oram deliver a smart and well-paced production, which brings out both the laughs and the horror of the original. Turner is brilliantly charismatic as the demented Padraic, his muscular arms waving guns as he inhabits a white, blood-stained vest, and he invests a note of reason into even his most crazed sentiments. And he caresses his dead cat with a love that seems hair-raisingly funny if you think of all the humans he has dispatched, and his lack of real relationships is cruelly linked to the fact that his father used to “trample” on his wife — literally. There is a temptation to comment once again on Turner’s attractive body — remember the fuss about his topless scything in Poldark? — but given that remarks about women’s onstage bodies are nowadays a no-go area, maybe we should apply the same rule to dishy men?

For the rest of the cast, Charlie Murphy also impresses as Mairead, the frustrated idealist who is as dangerous as the mad terrorist, while Chris Walley — making his theatre debut — as her gormless brother Davey and Denis Conway as the drink-loving Donny all give good support. As do Will Irvine, Daryl McCormack and Julian Moore-Cook as the vengeful if incompetent INLA hitmen. Although some of McDonagh’s later work is distressingly inhuman, here the exuberance of the language and the wildness of his critical vision carry the day. It’s a fabulous revival.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times