The Cocktail Party, Coronet Theatre

Thursday 24th September 2015

Once a giant of postwar British theatre, TS Eliot is now one of the most rarely performed modern playwrights. His work is seen as too long, too tedious and too difficult. Somehow his high seriousness is not in tune with today’s sensibilities. So this is a rare chance to catch a new production of his The Cocktail Party, which was first staged at the Edinburgh Festival in 1949 with Alec Guinness in the cast, and was one of Eliot’s most popular plays in bygone decades. So how does this play of metaphysics and psychoanalysis stand up to the passage of more than 65 years?

As you can tell by its title, The Cocktail Party begins like a typical drawing-room drama. The setting is the posh London home of Edward Chamberlayne, a well-off lawyer, and his wife, Lavinia. But instead of starting with preparations (mixing cocktails and so on) for the party, Eliot shows us a gathering that has gone awry. Earlier that day, Lavinia has walked out on Edward and he has tried frantically to cancel the event. Only a handful of friends have turned up: Alexander, aunt Julia, Peter and Celia. Oh, and the mysterious Unidentified Guest.

While Eliot gets a fair amount of comedy out of the scatty character of aunt Julia — played here with cheery panache by Marcia Warren — it soon becomes clear that this is no ordinary drawing-room entertainment. As the focus shifts to the Uninvited Guest, a larger perspective slowly becomes apparent. What began as a comedy of manners now turns into a much more symbolic, absurdist and religious drama. Eliot’s aim is not just to make us laugh; he also wants to heal our souls.

And there is a lot to fix in this family. Neither Edward nor Lavinia are satisfied with their marriage, and both have been having affairs with other characters. So Edward has been involved with Celia, a young debutant, and Lavinia with Peter, who is bound for Hollywood. It takes the combined persuasive powers of Julia and the Uninvited Guest — whose name is revealed as Sir Henry Harcourt-Reilly — to manipulate Edward and Lavinia into attending a meeting that is partly marital therapy and partly spiritual guidance, with a dash of metaphysics thrown in for good measure. At the same time, in the darkness of the background lurk the shades of ancient Greek tragedy (for buffs, it’s Euripides’s Alcestis).

Amid all the gloss, and the play’s unobtrusively poetic verse, is a portrait of a marriage that’s in trouble. At one point, Edward describes Lavinia as a “python” strangling the life out of him (a phrase that is echoed in John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger in 1956). But while Harcourt-Reilly says that his therapeutic method is “letting you talk as long as you please, And taking note of what you do not say”, he is less of a psychiatrist than a priest-like presence. In the end, while the central couple return to a recognisable normality, and Peter is a big success across the pond, Celia ends up paying the price for Eliot’s demented religious fantasies. Her gruesome martyrdom is clearly her creator’s dream of spiritual justice — and there’s something rather sickening about this. In the context of the play, Eliot’s lifelong obsession with the Crucifixion feels not only old-fashioned, but inhuman too.

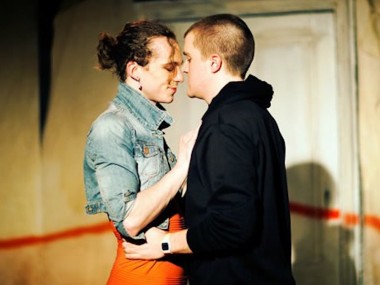

Abbey Wright’s stylish production uses the Print Room’s spacious new home in the circle of Notting Hill’s Coronet Cinema with good effect, and the architecture — originally by Victorian theatre designer WGR Sprague — suits the play’s classic status. Hilton McRae’s sombre and mildly sinister Uninvited Guest contrasts well with Warren’s sprightly and often hilarious Julia, while Christopher Ravenscroft’s Alexander is similarly excellent. Although Richard Dempsey looks a bit too youthful to fully convince as Edward, Helen Bradbury and Chloe Pirrie are fine as Lavinia and Celia. The same applies to John Wark’s attractive Peter. If all of the cast struggle occasionally with Eliot’s stately verse, it is the playwright’s rather grim religious ideas that are the most offensive, and dated, part of an otherwise enjoyable evening.

© Aleks Sierz

1 Comment

on Sunday 27th September 2015 at 10:49 pm