The Fastest Clock in the Universe, Hampstead Theatre

Thursday 24th September 2009

Behold the gleaming dark. At one point in this spirited and imaginative revival of Philip Ridley’s 1992 play, The Fastest Clock in the Universe, one of the characters says, “We’re all as bad as each other. All hungry little cannibals at our own cannibal party. So fuck the milk of human kindness and welcome to the abattoir!” Yes, well. As welcomes go, this is about as pleasant as a razor blade hidden in a cupcake — and perfectly apt for this sharp slice of East End gothic.

Set in a disused fur factory deep in darkest London, Ridley’s play begins by portraying the tangled domestic arrangements of thirtysomething Cougar Glass and his older friend, Captain Tock. Unable to face life, and the reality of ageing, Cougar holds regular birthday parties where he and the Captain pretend that he’s just turned 19. On this occasion, for example, Cougar has invited a young teenager, Foxtrot Darling, with the aim of seducing the boy. Like a vampire, he needs young blood. But, unknown to him, Foxtrot has his pregnant girlfriend, Sherbet Gravel, in tow. And when Cougar and Sherbet meet, sparks — if not exactly fur — begin to fly.

On Mark Thompson’s set which — with its stuffed birds, creaking doors and erratic electrics — seems to breathe the stale smells of cramped lives and demented dreams, the action unfolds slowly, like a creaky old fold-up bed, all blood stains and twanging springs. Cougar and the Captain’s master-and-slave relationship provides the psychological bedrock for the in-yer-face drama that follows, and their interchanges with their landlady, the old East End matriarch Cheetah Bee, outline in vivid detail the isolation and inwardness of their peculiar world, with its rituals and incantations. Like its distant inspiration, Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, this is a study that draws equally from social realism, absurdism and a visceral sense of the tragic.

As the guests arrive, this modern-day take on Jacobean drama quickly reveals, to borrow TS Eliot’s words about the 17th-century penman John Webster, the “skull beneath the skin”. Using the figure of Sherbet as a kind of Cockney truth-teller, Ridley slowly peals away the lies that have kept Cougar’s fragile self-esteem intact, and his menage together, thus exposing all the flaws of his frozen character. As the play plunges towards its inevitably violent climax, with shouts of “Blood! Blood! Blood!”, you’re left with an unforgettable impression of having witnessed both sweet perversity and the pleasure of cruelty.

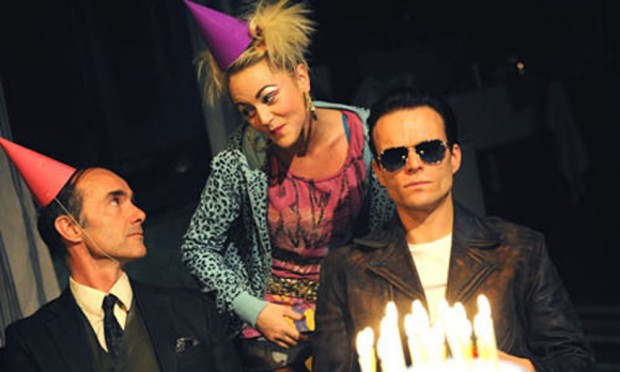

In Edward Dick’s thrilling revival, Finbar Lynch excels as the Captain, with his mix of paternal angst and servile charm, while Alec Newman’s neurotic Cougar is coiled up so tight you’d need to be a lion-tamer to handle him. It’s not a question of rubbing him up the wrong way; just touch the guy and he’ll bite. Newcomer Jaime Winstone is a mesmerising stage presence, gobby but sharp (Daddy Ray must be proud). Foxtrot (the role created originally by Jude Law) is played here by Neet Mohan as a naive and petulant brat, and Eileen Page as Cheatah winds things up when she comes on, at the end, looking like old Mother Time.

Part of the Hampstead Theatre’s celebrations of its 50th birthday, this dip into the venue’s back catalogue (Ridley is their most produced playwright) throws up one of contemporary theatre’s most intriguing and blackest of black comedies. Like a wry update on Dorian Gray, the play is a meditation on the cruelty of nature in general and the decay of the human body in particular. At the same time, it is a strong and convincing account of how the light of truth bursts out of the deepest darkness. Despite a slow beginning, this is a great evening.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk