Sarah Kane: an interview

Friday 1st January 2016

When Sarah Kane was still alive, it was vital to support her work — her style was so raw, so provocative and so innovative that many critics simply didn’t get it. Some even called for it to be censored. So it was important to support her, almost without question. But, when the 28-year-old playwright committed suicide on 20 February 1999, everything changed. Now, suddenly everyone loved her. Now, she was an icon. Now, she was a secular saint. Critics fell over each other to recant — it was like an episode from some religious war.

Wars breed anecdotes. And it soon emerged that everyone has a Sarah Kane anecdote. So here’s mine. It’s about the interview I did with her for the chapter on her work for my first book, In-Yer-Face Theatre: British Drama Today, and it may, or may not, be the last interview she ever gave. In my 1998 diary, there’s an entry for 14 September: Kane, 12 noon, SW9 (the name of a cafe in Brixton, south London, where we both lived at the time). The diary also shows that, in the previous week, I’d seen the Paines Plough production of Kane’s Crave (8 September), and soon afterwards I saw Mark Ravenhill’s Handbag (18 September). Oh heady days.

We met at SW9 because Kane lived just around the corner in a flat which she shared with her friend David Gibson at 6A Bellefields Road. I arrived early, and remember standing apprehensively at the bar — I was a bit tense, a bit nervous. After all, I was a fortysomething journalist and couldn’t help thinking that the character of Ian, also a fortysomething journalist, in her debut Blasted expressed her hatred of all middle-aged men. In fact, when I’d spoken to her on the phone to arrange the meeting, she laughed: “I seem to be meeting a lot of middle-aged men recently.”

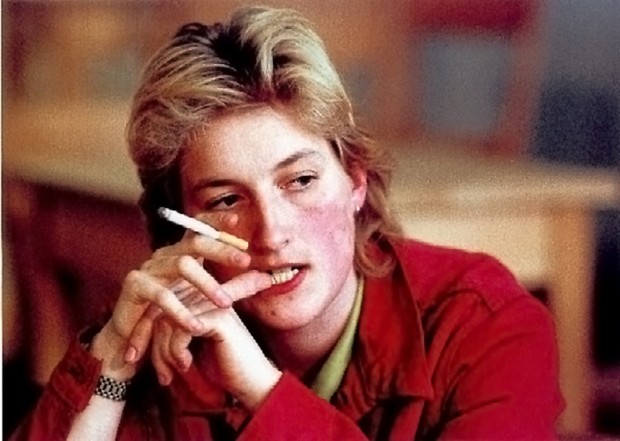

I was worried that she’d be as aggressive as her work suggested. I suppose this is an example of the biographical fallacy in reverse. In fact, when she arrived, right on time, she was smiling. Wearing a black leather jacket, and hip black clothes, she could barely disguise her sleepy eyes, and the fact that she’d just got out of bed. “Oh, it’s early for me,” she said. “I’ve been up all night writing.” It was the way she liked to work.

We drank coffee at a corner table by the window. The moment she sat down, she got out her cigarettes. She offered me one. No thanks, I said, I’m too afraid of cancer. “You’ve got more chance of dying from a heart attack from worrying about it,” she joked, lighting up. When Kane smoked, she held her cigarette behind her back so that the smoke wouldn’t blow into my eyes. This considerate behaviour reminded me that although her plays have lashings of violence, they are also full of gentleness. After all, her main theme is love.

Then Kane gave me back a copy of an academic article I’d written about Blasted and the politics of the new censorship, where the media leads the call for banning plays rather than, as in the past, the state (whose censorship of theatre ended decades ago in 1968). In her delicate handwriting, she’d made a couple of corrections: where I had written, “Kane deliberately sets out to create a godless universe”, she wrote: “I don’t know. God does make an appearance [in Blasted]. And there is life after death.”

Kane talked some more about her first play, pointing out that the final scene takes place in a metaphorical “hell”. “Don’t forget the stage direction that says ‘He dies with relief’,” she said. “Ian dies, so you think that’s the worst thing that can happen — then it rains on him.” It’s a moment that sums her sense of humour, bleak perhaps, but humorous definitely. And she enjoyed the fact that directions like this present a real challenge to directors of her work.

Showing me a passage where I had misquoted her, Kane corrected my garbled version by stating succinctly: “Theatre will always be a minority interest, but the lack of a mass audience is compensated for by the lack of direct censorship.” At various points during our meeting, which lasted about two hours, she would consult a small notebook, pointing out which journalists had misquoted her.

It was clear that Kane thought of her character Ian with a mixture of horror and affection. When I said that, as a middle-aged man, I recognised his psychology, and the way he tried to manipulate Cate, she was pleased. “Yes,” she said, “when I was at Birmingham, there was a middle-aged man on the MA and he defended my portrayal of Ian when the other students attacked it. And I thought that was brave of him.”

Of course, Kane understood that you can feel a sexual or a violent desire without necessarily acting on it. “It’s one thing to have an idea, it’s quite another to act on it. We all have some control over our actions.” But what about Cate? Well, she stressed the fact that Cate is not retarded, and — much as she loved this character — she was also a bit exasperated with her: “I mean, what’s she doing in that hotel room with Ian?” Still, Cate’s resilience was as important to Kane as her naivety.

When I asked Kane what she thought of the label “in-yer-face theatre”, she shrugged as if to say: “That’s your problem, mate, not mine.” Then she said: “At least it’s fucking better than New Brutalism.” No writer likes to be labelled as part of a movement, and Kane was especially sensitive to being categorised as anything other than a “writer”.

We talked about the performance of Blasted that I’d seen at the Royal Court. It was the second press night, and she asked me how many people had walked out. I told her that only a couple had left, but that many people had giggled nervously during the evening. She was pleased that the play had had a powerful effect, and told me that she had seen most performances.

Why did the critics hate the play so much? Kane explained their reaction by pointing out that “a play about a middle-aged male journalist who rapes a young woman and is raped and mutilated himself can’t have endeared me to a theatre full of middle-aged male critics”. She also felt that she’d had a hard time from critics because she was a woman. I disagreed. I think that because Blasted is such a powerfully written piece, experimental in structure and provocative in its portrayal of a contemporary English civil war, it made audiences uncomfortable, made them feel they were experiencing the emotions shown on stage. And that discomfort and disorientation confused the critics (poor souls) — so they took the easy way out, which was to attack her.

Kane felt that the emotional content of her work had been misunderstood. “Blasted is a hopeful play,” she said. She didn’t recognise herself in negative descriptions of her work. “I don’t find my plays depressing or lacking in hope,” she said. “But I’m someone whose favourite band is Joy Division because I find their songs uplifting. To create something beautiful about despair is for me the most life-affirming thing a person can do.”

Despite the fact that love was so important to her, Kane was also constantly aware of violence. She told me two anecdotes about life in Brixton. In the first, she’d been shopping in Iceland supermarket, and bumped into a black woman, who went mad and abused her: “She called me ‘a white bitch’. You know, black people can be as racist as whites.” And the other story was from when she once lived in Josephine Avenue, and was about a gay man who been attacked and arrived on her front doorstep gasping, with his head streaming blood.

Kane also told me a story from when she was at Bristol university. Planning to study playwriting at Birmingham, she was compelled to pay a small sum for private health insurance. She wrote on the back of the cheque something along the lines of finding it fucking outrageous that to enter an educational institution she should be required to pay for private health insurance, to which she was deeply opposed. I mention this because I now think that the most important thing about her life was not her suicide, but the fact that she got a First Class Honours degree and an MA in drama — she was an intellectual. She loved plays. She loved theatre.

Kane hated giving interviews. At the end of our meeting, she told me she didn’t want to do any more. “I’m a writer,” she said. “I’d much prefer if you could send me letters, and I’ll write my replies to your questions.” In the next couple of months, she sent me a couple of letters about her plays, then silence. I carried on writing my book and, just as I was finishing the first draft of my chapter about her, I heard she’d killed herself. For a while I was shocked and couldn’t write any more about her, and even wondered whether to put her chapter in the past tense. In the end, I left it in the present.

Looking back, our meeting seems to be a characteristic mix of helpful kindness and full-on violent imagination that, in my mind, is the essence of Kane. Yet what haunted me afterwards was the frankness and openness of her personality. “Go on,” she said, “ask me anything.” At the time, I didn’t ask half the questions I wanted to. I thought we’d have plenty of time to talk about her work — I was wrong. I didn’t realise she was already planning her suicide. In June 2000, I talked to Robert Gore-Langton, a Daily Express journalist who’d interviewed her father about her suicide. He told me that he’d expected him to be defensive, but that in fact he was totally open. “Go on,” he’d said, “ask me anything.”

Like most people, Kane was a complex and occasionally contradictory human being: equally capable of being polite and aggressive, of being an introverted garret writer and an extrovert fun-loving woman, of loving moody, doomy music and supporting Man United, a colourful club, a winner’s club, of talking about “sucking gash” and of longing for love and tenderness, by turns honest, perceptive, provocative, sentimental and, yes, quite in-yer-face. Sometimes.

© An earlier version of this article appeared as ‘Sarah Kane: a última entrevista’, Artistas Unidos, No 14, November 2005: pp 66-67.

Afterword

Vince O’Connell, Kane’s friend and mentor, tells me that she became a Man United fan at a time when the team was not doing very well: “I took her to her first ever football match, at Old Trafford, where United lost 1-0 to Tottenham. United were abject, Lineker scored a 30-yard thunderbolt! (Perhaps his only goal ever from outside the penalty area), and Saz started supporting United because she felt sorry for them. It was all Gary Lineker’s fault.”