In the Next Room, St James Theatre

Friday 22nd November 2013

Is there a danger that a show can be oversold? Sarah Ruhl’s In the Next Room sounds innocuous enough — until you read its subtitle: The Vibrator Play. Marketed as the most provocative drama of the year, its theme is female sexuality in the Victorian era, and yes, it’s all about the discovery of the joys of orgasm. Now premiering in London, after a Broadway production that garnered Tony nominations, does this production, which is directed by Laurence Boswell, live up to the hype?

Set in a wealthy spa town just outside New York at the end of the 19th century, the story dwells in the home of one Dr Givings, who treats many women, and even some men, for hysterical symptoms. What’s amazing is that he uses an electric vibrating machine to give his patients orgasms, or in the language of the time “paroxysms”, and thus relieve the pressure on their wombs (yes, as you’d expect, the science really is pretty dodgy). Not only are his patients, such as Sabrina Daldry, sexually frustrated, but so is his wife Catherine, a new mother whose milk is inadequate, which means that a black wet nurse, Elizabeth, has to be employed, thus adding the issue of race and class to that of sexuality. Into this comedy of manners other characters, notably the nurse Annie and the painter Leo, drift in, elaborating the themes of more overt sexuality, both gay and straight.

Much of the comedy comes (oops) from our image of the Victorians as a straight-laced people, with the women especially naive and repressed. From the perspective of our more knowing age, they seem like creatures from a different planet, the women ridiculously innocent and the men absurdly patriarchal. This provides a lot of simple laughs and the transformation of Sabrina from chilly depression to blooming joy is heartwarming enough.

The case of Catherine is more complex. Seeing the effects of the new wonder machine on her husband’s patients, she naturally wants to try out the medicine. But Dr Givings says that his medical principles won’t allow him to treat his own wife. So Catherine decides to sample other avenues of exploration, and there are some interesting and tender scenes of female friendship to give the comedy some depth. Yet none of the psychology is convincing, and I had my doubts about the writing too.

Ruhl’s literary style has a stilted, awkward quality, part declamation and part archaic formulation. This might be her attempt to evoke a long-lost age, or to get a sense of comic brio from deliberate decorum, but to me it just feels odd: surely, no one ever spoke like this. Unbelievable as it is, the language has the advantages of clarity, if not of subtext and subtlety. The play is basically a documentary dressed up as light entertainment.

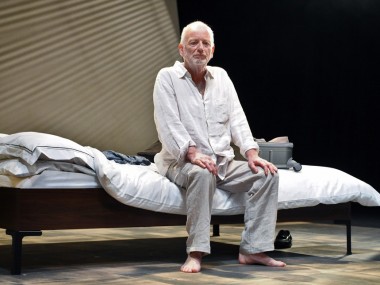

Still, Boswell’s sprightly production has a charming delicacy and the jokes are crisply delivered, and neatly wrapped up. On Simon Kenny’s split-level set, with the doctor’s surgery symbolically pressing down on the family’s living quarters below, a solid cast is led by Natalie Casey as the kooky Catherine and Flora Montgomery as the awakened Sabrina. Good support from Jason Hughes as Dr Givings, Sarah Woodward as Annie and Madeline Appiah as Elizabeth. But the play feels too long, too sunny and too superficial to deliver any real paroxysms. Definitely over-hyped.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk